Absolutely Dreadful

Penny Dreadfuls, Serial Fiction, and the Return of the Cheap Printed Word

The penny dreadful landed on a newly literate population desperate for thrills…

The penny dreadful has always been misunderstood.

The name itself suggests something disposable: crude thrills, lurid covers, cheap ink. And yes — there was plenty of that. But the truth is more interesting, and more uncomfortable. Penny dreadfuls were not cultural accidents or literary dead ends. They were the product of several forces colliding at exactly the wrong — or right — moment in history.

Literacy was rising across Britain. Printing was becoming cheaper and faster. Cities were swelling, anonymising, and darkening. Every week brought another terrible tale from a dank back alley. Newspapers had discovered that crime sold far better than sermons, while gothic fiction had already proven that fear could be beautiful if you dressed it well enough.

What emerged from this mix wasn’t “trash,” but a new form of serialized storytelling designed for a world that no longer felt stable.

The penny dreadful didn’t invent terror. It industrialised it.

The Penny Dreadful as Cultural Mirror

Penny dreadfuls were magpies. They pulled freely from everywhere: the melodrama of gothic novels, the sensationalism of tabloids, the procedural detail of court transcripts and police reports. Murderers, monsters, fallen women, corrupted priests — not as pure fantasy, but as exaggerations of what readers already suspected was happening just out of sight.

Crucially, these stories arrived in fragments.

Delivered weekly — often every Saturday — penny dreadfuls mirrored how people experienced reality itself: incomplete, ongoing, unresolved. You didn’t consume them in one sitting. You lived alongside them. Characters aged with you. Danger returned at regular intervals. Fear became habitual.

Your dreadful from the news-seller was as much a part of everyday cultural life as church.

This wasn’t escapism. It was pattern recognition.

“Delivered weekly — often every Saturday — penny dreadfuls mirrored how people experienced reality itself: incomplete, ongoing, unresolved”

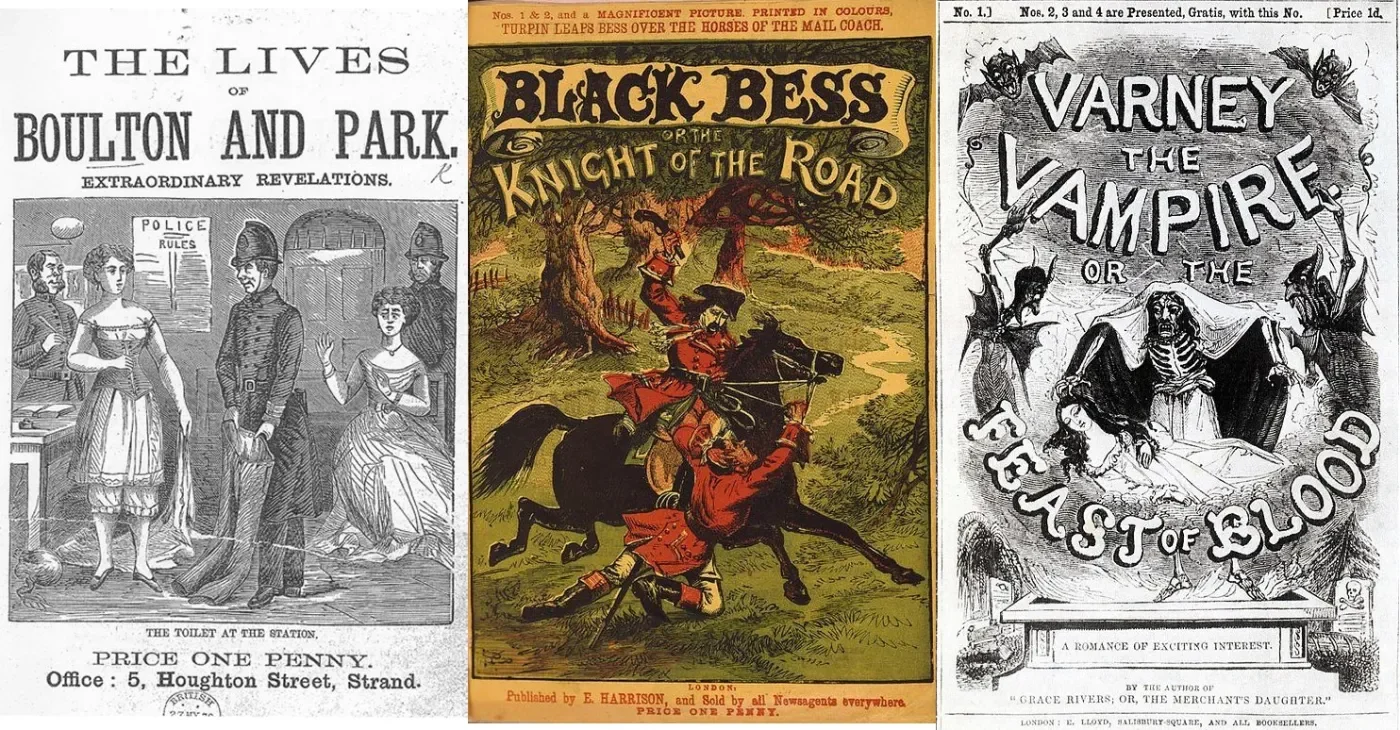

EEEK! Thrills and chills from the dreadful archives…

Serial Fiction and the Performance of Truth

Serialization did something else too: it created intimacy. A rhythm. A sense that the story was unfolding with you, or beside you, rather than being delivered whole. It’s difficult now to imagine the cultural power of a serialized writer — half of London pacing up and down, waiting for the next instalment.

And this rhythm wasn’t confined to the streets.

When Sherlock Holmes appeared in The Strand Magazine, serialized fiction crossed an invisible boundary. Holmes demonstrated that episodic storytelling could be clever, respectable, and authoritative — even frightfully upper-middle-class — while retaining suspense and immediacy.

More importantly, Holmes established something essential: procedural belief.

Dates mattered. Addresses mattered. Tone mattered. The illusion of documentation became part of the pleasure. Readers weren’t asked to suspend disbelief; they were encouraged to audit it.

Personally, my adoration for Conan Doyle has curdled over time. There is a great deal of Holmes being very, very clever, followed by a conveniently timed character who arrives to explain everything. And once the public demanded Holmes be resurrected from the Reichenbach Falls, there’s a lingering sense of “will this do?” about the later stories — thinner, less invested.

Still, the mark Holmes left on serialized fiction is undeniable.

From Penny Dreadful to Modern Casebook

This is where The Annotated Casebooks of Professor Manton Marble enters the tradition — not as revival, but as continuation.

The Annotated Casebooks of Professor Manton Marble—The Death at the Door is a serial in the oldest sense, and a deeply post-modern one. It doesn’t modernise the penny dreadful by sharpening the gore or updating the monster. It modernises it by updating the lie.

The book’s off-screen figure, Hamilton Earle, is not simply a narrator. He is an archivist of impossibility. The casebooks — discovered amid the dreary paperwork of a dark London library in the 1920s — arrive layered with footnotes, annotations, and editorial interruptions. This is a deliberate over-performance of credibility.

The cases themselves are fantastic. But when shipping manifests, restaurant bills, and marginal notes begin to suggest that it all actually happened, the question becomes unavoidable:

What are you meant to believe?

Why Footnotes Matter in Modern Storytelling

We live in an age obsessed with proof — or at least proof enough. Screenshots circulate as evidence. Comment sections rewrite narratives in real time. Wikipedia edits become ideological battlegrounds. Authority is no longer centralised. There is no atomic clock. No perfect kilogram locked in a vault.

Truth now belongs to whoever performs it best.

The footnote has replaced the omniscient narrator.

Look at Infinite Jest. Hundreds of pages of footnotes, until the question of why footnotes exist becomes the point itself. Explanation collapses into excess. Meaning frays.

Manton understands this. His annotations don’t reassure — they disturb. They mimic the apparatus of scholarship, journalism, and bureaucracy, then quietly undermine it. The result isn’t comfort, but unease: the sense that truth may be buried beneath too much documentation to ever fully surface.

At some point, you begin to wonder whether Earle hasn’t simply gone mad in his lonely library — driven there by the attempt to prove that fiction was fact all along.

In this sense, Manton is closer to the penny dreadful than to the modern novel. Both understood that belief isn’t created by a single idea, but through the relentless accumulation of loosely related ones.

The Death of Print — or the Death of Scale?

It’s fashionable to say that print is dead. What actually died was scale.

Mass print relied on advertising, broad attention, and centralised distribution — all of which have collapsed. But cheapness and physicality are no longer enemies. They’ve simply changed hands.

Print didn’t vanish. Ubiquity did. What’s returning now resembles the original serial tradition: niche, intentional, ritualistic. Stories delivered in parts. Objects meant to be kept. Readers who don’t want everything — just something to follow. If you saw our recent writing about committing to the real, you’ll recognise where this serialization comes from. Yes, it will live digitally — but we hope the same blood runs through it as once did through Varney the Vampire.

If enough interest stirs, those instalments may yet be bound into paper and thrust, screaming, into the physical world. We also suspect it could make a rather good graphic novel.

The Future of Serial Fiction Is Fragmented — Again

The penny dreadful never truly disappeared. It lingered. It waited.

We’re living through roiling times not unlike the birth of the modern age — fragmented truths, anxious cities, competing narratives. All Jack the Ripper, Baker Street, and Castle Dracula.

Today, serialization lives in newsletters, audio episodes, limited print runs, and annotated texts that demand attention rather than scrolling. Its survival doesn’t depend on mass appeal. It depends on commitment.

The Death at the Door will unfold in this spirit — not as a product to be consumed quickly, but as a case to be revisited, argued with, annotated, and slowly believed.