Forget it Jake…

The gumshoe is dead. Who killed him? Probably a little of all of us. Who replaced him? Well, that’s scarier still.

“As American as a sawn-off shotgun”

Dorothy Parker on Dashiell Hammett

Seems even the Queen of Acid thought the first true gumshoe scribe was pretty hard-boiled!

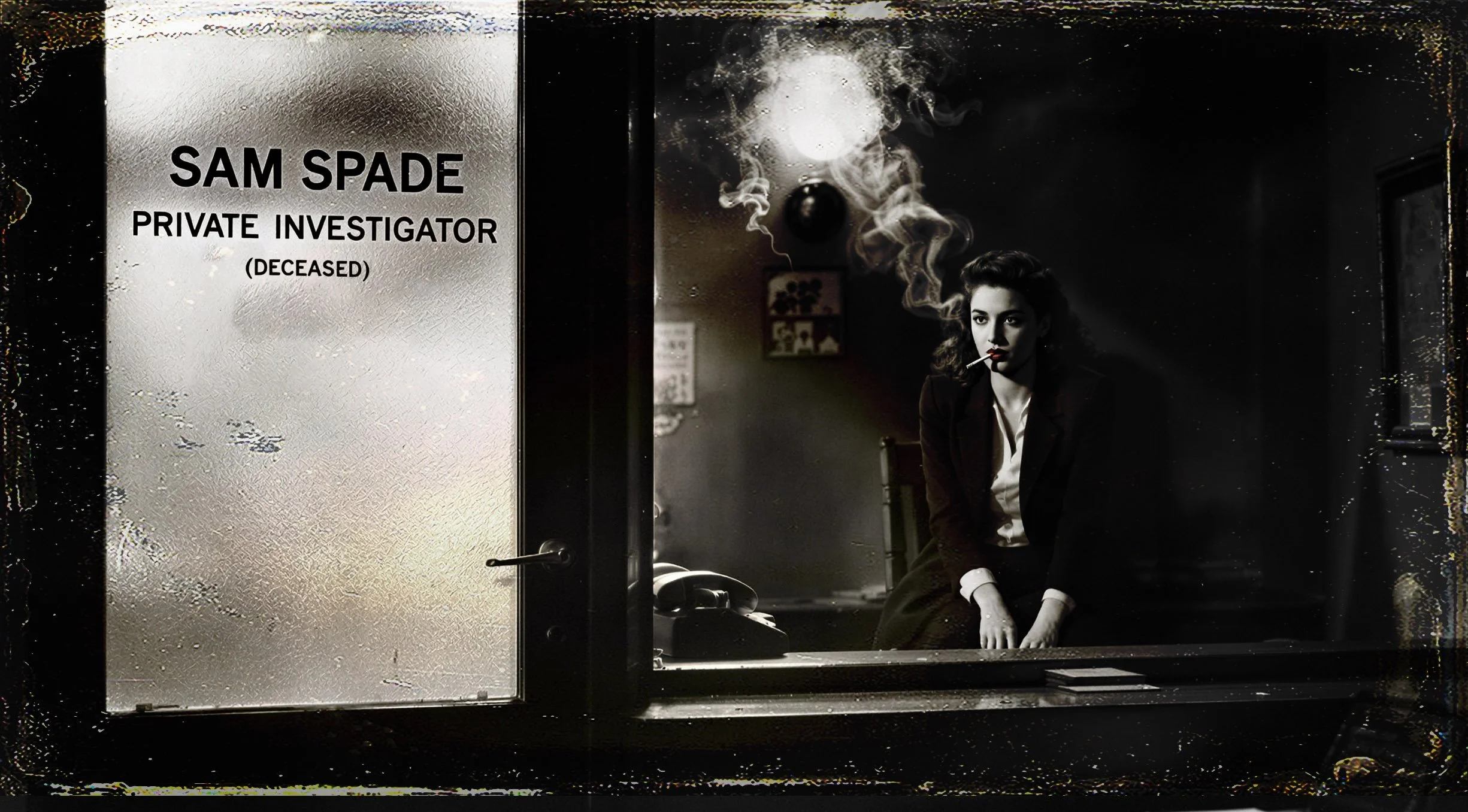

We all know the tropes (well, anyone over 30 maybe). The air in his office is thick enough to need bellows to find a seat. There’s a permanent cocktail of stale cigarette smoke, spilled whiskey, and the creeping cold of despair that seeps in from the rain-slicked street below. The put-upon secretary at the tiny reception area rolls her eyes and waves you through.

Welcome to the world of the private detective — shamus, gumshoe, man on a mission.

Cynical, a smart-ass… sure, but he’s a man with a code, not a badge. His only authority comes from a cheap license in a worn leather wallet and the weight of the shoulder-holstered pistol. He is Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade or Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, the original anti-hero, fighting a corrupt world with the only tools he has: wits, fists, snark, and a stubborn, suicidal belief that a single, broken man can still find a sliver of truth in a city built on lies.

He’s decent to his beat police, rude to their superiors. Incapable of love, because every dame he comes across is up to something — but he’ll save them nevertheless. He has no problem with race, because he’s pretty far down the list too, and he hates a bully — which is why he’s always on the side of the little guy. The swells may pay better, but their money leaves a bitter taste.

He didn’t save the world. He barely saved himself. But in that fragile space between duty and despair, he became something new in literature: the first antihero.

Now, cut to today. Today’s hero doesn’t have an office; he has a secure satellite link. He doesn’t drink cheap whiskey; he maintains peak physical condition — and smoking? Forget it! His authority comes not from a personal code but from a redacted government file, an invisible agency that grants him the power to operate outside the law, for the law. He is the ghost in the machine. And he should terrify us far more than the man with the bottle on his desk.

I knew the moment she walked in my office, she was gonna mean a whole heap of trouble

…my trouble

Writers like Dashiell Hammett (The Maltese Falcon) and Raymond Chandler (The Big Sleep) carved out a world that was recognisably our own — too corrupt to be romantic, too human to be pure.

The reason Hammett’s prose rang so true? He was a detective, for the Pinkertons. And Parker was right — his dialogue sounded like how people actually spoke. He knew that lowlifes could have morals and that the real crooks lived in mansions. He knew that women weren’t dumb broads — they were smart, often the smartest in the room, and could fight as dirty as was needed to survive in a man’s world.

Their detectives, Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe, were not good men — at times, the polar opposite. But they were honest men, at least by their own warped moral compass.

In a crazy way, they wanted justice — real, actual justice — but the world they lived in didn’t reward virtue; it punished it.

So they fought fire with fire: lies for lies, violence for violence. And OK, they might not get justice as such, but they could even up the scores, and in the real world, that has to do.

“Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean. He is the hero; he is everything. He must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man.”

Raymond Chandler

That paradox — integrity in an immoral world — defined the gumshoe. He was the battered conscience of a society that had lost its own.

And the great and the good hated him for it, because he didn’t just know you were a hypocrite, a crook, and a fraud — he told you to your face. And that’s why we loved him: because we wished we had that same moxie.

These things will kill me, the sooner the better

Seems everything in this noir world was a symptom, not a style.

The trench coat, the whisky in the desk drawer, the cigarette smouldering in the rain — all became clichés later, but they began as confession. Sam Spade wasn’t about appearances, but about attitude — if you’ve spent so long in the seedy underside, what’s the point?

And the femme fatale was usually the nemesis, not the corrupt governor. Hammett’s books are full of well-dressed carpetbaggers — not smart, but with a phalanx of brute morons to get things done. Chandler’s match wasn’t merely a seductress; she was the embodiment of post-war disillusionment — the dangerous truth that desire and destruction often wear the same perfume.

The heavy drinking, the sleepless nights, the wisecracks: all coping mechanisms for men who understood that the game was rigged, but played anyway.

Noir fiction was America waking up with a hangover after the American Dream wore off — and creating (aided by the epochal portrayals of Bogart et al.) a relatable modernity stripped of its illusions — any illusions, really.

The Place: Chinatown

The Crime: The Death of the Detective

Three decades later, the gumshoe came back for one last case — and it destroyed him.

“As little as possible.”

— Jake Gittes on his time as a District Attorney’s assistant.

So Jake became a detective, seeing as he couldn’t do anything about the corruption in LA as part of the law itself.

Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974) reimagined the hardboiled detective for an America reeling from Watergate, Vietnam, and moral exhaustion. The genius of it — among many things — was to put those modern attitudes into the original PI’s time.

Jack Nicholson’s Jake Gittes begins the film as the perfect descendant of Chandler’s Marlowe: slick, cynical, smart enough to think he’s in control. He’s the private eye as entrepreneur — selling truth to the highest bidder, sleeping well enough at night. He’s thrown in the towel about it all, wryly observing, “Politicians, ugly buildings, and whores all get respectable if they last long enough.”

That is, until Evelyn Mulwray walks in. Beautiful, but not a femme fatale — smarter, quicker with a one-liner than Jake even. As trouble goes, she’s all of it and more. And it’s his naivety, his belief he can avoid any real personal entanglement, that becomes his undoing. He thinks he’s in total control — until he realises he doesn’t have any.

The conspiracy Jake uncovers — civic corruption wrapped around a personal horror — reveals that the real rot isn’t in the city; it just reflects it. It’s in the family.

When he learns that Evelyn Mulwray’s daughter is also her sister, the revelation hits not just as shock, but as existential defeat: even innocence has been compromised. It’s a testament to Nicholson at the height of his powers, delivering a character arc that should take novels but happens in two hours.

By the film’s end, Jake has become a witness to the futility of moral action. He solves the corruption case, he unmasks Noah Cross for what he is, but justice is impossible.

He exposes the truth, and it changes nothing.

“Forget it, Jake — it’s Chinatown.”

Arguably the greatest last line in film history (call it a draw with Some Like It Hot). It’s not just a dismissal, but a eulogy.

He’s not a saint, but he tried. But he’s done. The girl is dead, the system won, the wicked endure, and noir grew up — or gave up.

Forget it indeed.

The Split: Klute and Dirty Harry

The decade that followed fractured the investigator into two new archetypes.

In Alan J. Pakula’s Klute (1971), Donald Sutherland’s private investigator finds himself drawn into the orbit of Bree Daniels, Jane Fonda’s escort who sees more clearly than any man around her. In Sutherland’s masterly cipher of a performance, the gumshoe is passive, almost obsolete — emotionally stuck. No code, no belief — passing true morality into the hands of the woman, a prostitute no less, he can’t save. Again, Fonda is amazing here — she’s no victim; she’s the only one with anything close to a moral compass.

Meanwhile, Dirty Harry (1971) takes the opposite path. Clint Eastwood’s rogue cop channels the same cynicism and isolation as Marlowe, but with state power behind him — well, the state and a huge gun. We cheer him on, because he wins. The state fails Scorpio’s victims (although apparently the technicality that lets Scorpio walk in the final act is total BS).

Still, simple solutions are sometimes the best, right?

Harry Callahan gets results. He does what Jake Gittes couldn’t. But his victories come at the cost of democracy itself. Thw whole ethos really is contained in this early exchange

Mayor: Callahan… I don’t want any more trouble like you had last year in the Fillmore district. You understand? That’s my policy.

Harry: Yeah, well, when an adult male is chasing a female with intent to commit rape, I shoot the bastard — that’s my policy.

Mayor: Intent? How’d you establish that?

Harry: When a naked man is chasing a woman through a dark alley with a butcher knife and a hard-on, I figure he isn’t out collecting for the Red Cross.

[leaves]

Mayor: I think he’s got a point.

Together, they mark the fork in the road:

The moral detective died; the authoritarian enforcer was born.

From Outsider to Institution

By the 1980s, the gumshoe’s office had closed for good.

The private eye — once the outsider, the conscience of the street — was replaced by institutional protagonists: the FBI agent, the military operator, the tech-savvy analyst. Our fiction shifted from men haunted by power to systems justifying power. We traded mystery for procedure, conscience for policy.

OK, Sam Spade was never going to win the war. Whatever small battles he scraped through on points, the gumshoe was never meant to win big — but at least he asked the question.

Think about the ’70s and ’80s on TV (if you’re old like me): it was wall-to-wall PIs. Columbo, Rockford, Magnum — even Murder, She Wrote put in a decade-long shift.

My favourite detectives of the last few eons? House and Cracker — one was a psychologist, the other a doctor.

Now everything is agency versus agency and big shootouts, why walk off into the sunset when you can blow it up?.

Ed’s note: Hey, I’m not knocking any of that — that TV ain’t gonna watch itself — but just how many people work in the CIA?

Wake Up People

“I think it’s cute you think you have any jurisdiction here.”

Agent Walker to just about anybody

In Walker Awake, one of our first titles, that question resurfaces — not in the back alleys of Los Angeles, but in the corridors of an organisation that exists beyond oversight: Inland.

Walker isn’t an outsider. He isn’t “an agent of,” like one of our heroes, Dale Cooper.

He is the system.

You can probably tell I grew up reading 2000 AD, where its most famous character, Judge Dredd — a future cop who was literally judge, jury, and pretty often executioner — would simply state: “I am the Law.”

As ever, the Human League said it best:

You’re lucky I care

For fools like you

You’re lucky I’m there

To stop people doing the things

That you know they are dying to do

You know, I am no stranger

I know rules are a bore

But just to keep you from danger

I am the law

However, like Gittes, he’s beginning to understand that the moral rot runs deeper than anyone admits. He’s a modern descendant of both Marlowe and Harry Callahan — the man caught between conscience and control, haunted by the knowledge that his authority is built on silence and brute force.

If the gumshoe once symbolised the individual’s fight for justice, Walker represents something more dangerous: the state’s belief that justice can only exist through control.

Walker has woken up, halfway through his life. Who is Inland? Are they good or bad? Is that even a thing? And even if they are for the greater good — “What if someone full of malice and narcissism took control of it?”

That sounds like a very familiar theme in the world right now.

Watching the Detectives

Nostalgia is a powerful thing.

I’m getting a little tired of agencies fighting agencies, rogue operatives vowing “to bring it all down.” Even superheroes have to get into teams these days. I don’t know — maybe you need government funding to build those big hovering things.

This is why I loved the recent film The Batman. Batman was (and should be) a detective. I mean, it’s DC Comics, for crying out loud.

It’s why Walker has to be in the (if alternative) 1950s. Set now, he wouldn’t wake up smoking in a diner — he’d be on a laptop in a Starbucks near the Pentagon. And where’s the fun in that?

If we believe the movies, every day hundreds of gun battles are going on in public spaces. Can’t we have Sam Spade back? The little guy, the crooked cop, the mobster and his henchmen — plus, of course, a deadly smart dame — and the millions of combinations of those that probably are happening each day?

“Forget it, Jake.”

I won’t. Not yet.

See you in 1950s Texas.