Groan Alone: Why Every Castle is Haunted

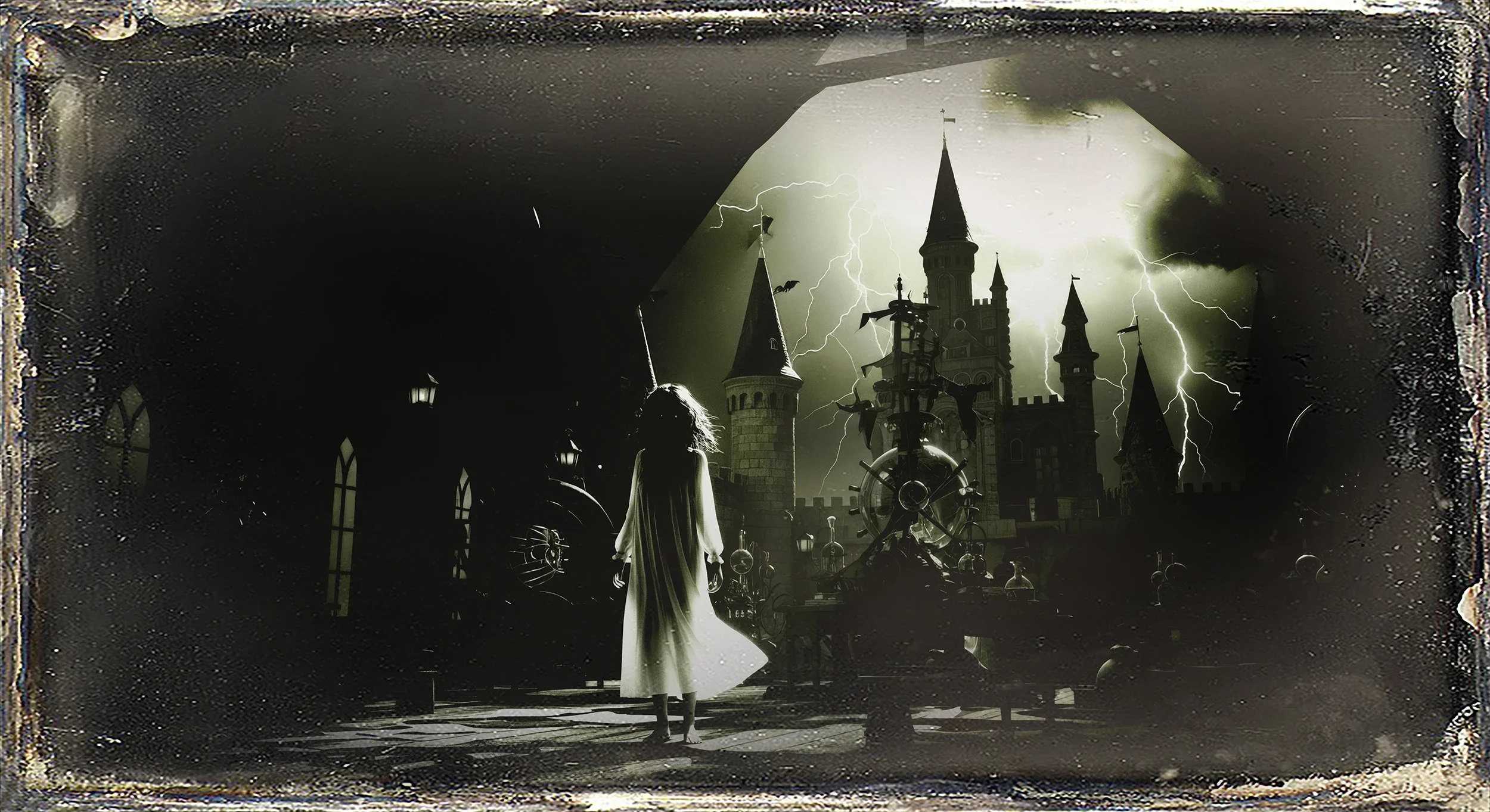

A cast of weird and crazy Gothic characters roil around a the towering presence of a great, living castle. Sound familiar?

Toys in the Attic: Peake’s ideas of worlds within worlds always stuck with us.

Well no, it’s not an overview of Narcisa Before Narcisa, but Titus Groan by Mervyn Peake — the first of his amazing Gormenghast novels. Yes, you can hear echoes of soooo many influencers, but if Narcisa owes a debt to any single work of gothic imagination, it is surely this one.

But we’re not alone in that we think…

The People in the Walls

Peake’s characters are grotesques, and all the more unforgettable because of it.

Steerpike: the sly kitchen-boy who clambers and claws his way toward power, the smile always a little too sharp, until his overreach collapses his schemes over him.

Fuchsia: lonely and blazing, hiding in the rafters with her dreams, a furious, melancholic spirit. A haunting ghost that’s still alive.

Swelter: the monstrous cook whose appetite is as terrifying as his presence. A huge raging Id, a warlord with his very own fiefdom disguised as a kitchen.

Flay: dry as bone, all angles and servitude, ageless and forever ancient, with clicking knees.

These are not characters who ask to be liked — and if they did, you wouldn’t anyway. Yet for all the grimoire of it, all its fantastical imagery, they are very real. They are very… us.

When I was shaping Narcisa, I recognised how much I had learned from this: that sometimes a figure can be more feltthan understood, and that grotesquerie can carry both menace and tenderness. A giant wolf, an imperious aunt, children whose questions undo the story itself — all part of the same inheritance.

“Gormenghast is not a setting, not really. It is perhaps the book’s most important character…

The Houses of the Unholy

Gormenghast is not a setting, not really. It is perhaps the book’s most important character.

Its towers rise in endless dust, its corridors knot into labyrinths, its rituals grind on with absurd, crushing gravity. Instead of resisting the great trees around it, it simply lets the branches go through it — huge boughs a perfect spot for the Groan sisters to take tea and bicker about their woeful lot.

The castle is very much alive, though it never speaks. It is a world in stone, and its inhabitants are bound by it like moths sealed inside a mason jar. Steerpike perhaps realises more than anyone: if you can’t escape, then you must rule over it.

The castle in Narcisa may be smaller, stranger, slipperier — but it shares the same DNA. Why shouldn’t it shift its shape? What’s the point of being unknowably old if you don’t learn a few tricks? It stores memory in its walls, it demands rituals, it bends to storytelling.

And here, perhaps, is Peake’s most important gift: that a place can haunt as powerfully as a person.

The Wasted Girl vs. The Self-Made Girl

Nowhere is the kinship clearer than between Peake’s Fuchsia and my own Narcisa.

Fuchsia is a girl of wild hair and wilder moods, who burns with imagination yet never finds her place in the ritual-strangled halls of Gormenghast. Her end is heartbreakingly accidental:

“The waters received her without a sound.

She had fallen awkwardly, and her head struck a spar of timber and she sank.

A few bubbles broke the surface, then the grey flood closed again.”

Fuchsia is consumed by the castle itself, her fire extinguished in rain and flood.

Narcisa, by contrast, shares Fuchsia’s awkward beauty, her imaginative defiance, her tendency to make a great hash of things. But Narcisa wields fire and irony where Fuchsia yearns and sulks. She takes the stage — even a courtroom becomes her theatre. Where Fuchsia is erased, Narcisa authors herself.

Fiends of Flesh and Blood

Most gothic fiction leans on the classics: vampires, witches, revenants of one form or another. Peake gave us something else. His dread seeps in through atmosphere: the futility of endless rituals, the absurdity of lives trapped in stone, the way tradition itself becomes a slow suffocation.

These aren’t glamorous creatures flitting around the full moon. They are bitter, petty, spiteful, scheming…people. Flesh and blood. Peake knew the most gruesome fiends are more likely to be human than phantom. Which makes them scarier, because phantoms don’t exist.

That sense of dread is what Narcisa borrows most fully. Menace does not always arrive with fangs or fire. Sometimes it’s the silence thickening in a corridor, the look across a dinner table, the sense that doom is not approaching but already here, quietly seated beside you.

The Creak in Every Corridor

It would be wrong to say Narcisa is a retelling of Gormenghast. It isn’t. Different time, different myth, different bones under the floorboards.

But influence is never simple. It is less about borrowing than about being haunted. Peake’s novels exist in the background like a dream you half-remember. The way his characters loom, the way his castle exhales, the way absurdity and tragedy entwine — these echo through my own work whether I invite them or not.

We do not escape our literary ancestors. Quite often something pops out of the page you’ve just written. Not a repeat, but an echo.

Return to Gormenghast

If you’ve read Titus Groan or Gormenghast, you may recognise some of their shadows in Narcisa. If you haven’t, I almost envy you: that first encounter with Peake is a true initiation into gothic bonkers-ness.

I once re-read the whole saga in a single indolent holiday day. It felt very odd to take a trip to the deep, dank halls of Gormenghast while lounging in the Tenerife sun. But that creepy castle is compelling. At least to visit — living there would drive me mad.

And if nothing else, it makes me wonder what other ancestral books each of us carry.

Which works rewired your imagination, slipped under your skin, and still shape the way you see the world now?

I’d love to know — because in the end, all our libraries are full not just of books, but of ghosts too.

Don’t forget, the scene-setting opening chapter of

Narcisa Before Narcisa, ‘So Scheherazade Began ‘

is available to read here!

Subscribe to Pressebande, our monthly dispatch, and you’ll be the first to read new excerpts, see behind-the-scenes, and join us as we build the Datura library from the ground up.